Many people think that scuba diving in BC is a summertime sport, when in fact it’s a four-season sport, with a fascinating variety and cycle of life across the seasons. Drysuits make it possible to dive comfortably all-year round.

A drysuit is a technical piece of equipment that a diver must operate and manage actively, unlike a wetsuit, which is worn passively for exposure protection. Drysuits have advantages over wetsuits, but they introduce additional risks. A drysuit diver must develop a higher situational awareness and new motor skills to operate their drysuit effectively & safely.

A drysuit is a sealed air-vessel, with the seals being at your neck and wrists. The suit is connected to the regulator’s first stage and to the air cylinder by a low-pressure hose, just like the inflator hose on the BCD. The inflator button is located in the middle of the chest. The drysuit also has an exhaust valve, usually located below the left shoulder. The inflator and exhaust valves are both deployed using your right hand. This is because you need your left hand to operate the BCD.

A drysuit diver must actively add air to, and exhaust air from their drysuit throughout a dive, much like they do with their BCD. However, a drysuit is not a substitute for the BCD and should not be used as the primary vessel for buoyancy control underwater. There are several reasons for this, the first one being that a drysuit is not designed or constructed to act as a primary buoyancy control device. It has multiple possible failure points that could result in a catastrophic flood. It exhausts air more slowly than a BCD. A too-large air bubble inside a drysuit can shift quickly and dramatically, throwing a diver off-balance and risking an inverted, out-of-control rapid ascent. And it’s impossible to exhaust air from a drysuit when the diver is in an upside-down position. Therefore the safest way to operate a drysuit is with a minimum amount of air inside it to offset a squeeze and allow the diver to feel comfortable, with free movement of arms and legs.

At VSds, we train clients to dive in a shell-style drysuit, which itself provides no thermal protection. The diver wears layers of long underwear, fleece and socks. These undergarments plus the air in the suit provide the insulation.

The PADI Drysuit Specialty course will introduce you to drysuits in general, and train you to operate a drysuit while adapting your buoyancy control technique. It’s a one day, two-tank dive, with a brief course manual to read prior to dive day. If you want to rent a drysuit in the future as a certified diver, then you will need to present this C-card as proof of training.

_________________

Prospective divers often wonder what the water temperature is around Vancouver, and whether they should train and be certified to dive in a drysuit. The simple answer is that the water’s always cold and that a drysuit will keep you warm much longer than a wetsuit can. So you should learn to dive in a drysuit and wear one all year round.

The water temperature at depth doesn’t fluctuate very much thoughout the year, with a minimum temperature of around 7-8C in February and the maximum around 13C in August. In the summertime, there’s a thermocline with a surface layer of warmer water reaching about 16C. But divers pass through the thermocline on descent, down into the deeper, colder water.

Wetsuit divers will usually only dive comfortably in the July-September time frame, when the water temperature is warmest and, most importantly, when they can warm up in the sun between dives. For the rest of the year, wetsuit divers can’t warm up between dives, so they get cold faster on the second dive. This results in a higher risk profile and short second dives. Often the wetsuit diver cancels the second dive .

Meanwhile, drysuit divers must deal with the opposite problem. They can stay toasty inside the drysuit between dives when there’s snow on the beach in winter, but risk sweating and overheating when the air temperature is above 15C. They enter the water to cool off, and get chilled by the perspiration evaporating on their skin.

In the wintertime, I recommend that divers wear a base layer of warm, perspiration-wicking thermals, with two pairs of the thickest, warmest Arctic socks. I also recommend wearing a lower-back heat wrap that will keep your core warm all day. A double layer of fleece is worn over top of this base layer.

In the summertime, a diver can wear shorts and a t-shirt, or a light base layer, under the fleece.

Serious divers will tend to use dry-glove systems rather than neoprene gloves. Hands will stay warmer, longer.

Drysuits are much more expensive to buy than wetsuits. A good quality drysuit, with accessories including a hood, boots and dry gloves will cost $2,000-3,000. Most dive shops will rent drysuits for around $50-75/day, marginally more costly than renting a wetsuit.

]]>

I strongly recommend that you check out Divers Alert Network. DAN not only offers dive travel insurance, it's a major source of medical information and dive accident statistics.

Click on the link to visit Divers Alert Network

]]>

Vancouver Scuba diving school is not a retail dive shop and we don't sell dive equipment. But we know that diving is an expensive sport and we're pleased to announce that VSds clients will now get a 20% discount off everyday retail prices on all their gear purchases at partner dive shops, when you're enrolled in any of our courses.

Typical retail price ranges for core diving equipment are as follows:

- Exposure protection: $2,500+ for drysuit, spare wrist and neck seals, zipper wax, booties, hood, dry gloves, fleece undergarment, base layers of long underwear, heavy arctic socks.

- Buoyancy Control Device (BCD): $400-700

- Regulator: $1,000-1,500+

- Critical accessories group: $1,000+ for compass, dive computer, knife tool, dive light and backup light, safety/signalling devices.

- Personal gear group: $300+ for mask, snorkel, fins, spare straps.

- Incidentals: $300+ for gear bags, bins, tool box and tools, spare parts, spare hoses, etc.

The money you can save as you equip yourself for diving can offset much, if not all, of your course fees when you sign up with Vancouver Scuba diving school.

]]>During my 30+ years of diving, I've encountered risk-takers, risk-avoiders, thrill-seekers and the risk-oblivious. My goal here at VSds is to guide clients to become proficient risk managers.

Risk can be defined as the probability (or uncertainty) that some undesirable event will occur, and the corresponding consequence(s) of that event.

In my research for this blog, I've come across some useful concepts and statistics that will help to identify and quantify the variety of risks you'll face as a novice scuba diver. There are both knowable and unknowable (variable, random) risks on every dive. A competent diver will be aware of the major and minor knowable risks, will plan and execute their dives accordingly, and will be mentally prepared with contingency plans to balance and manage known risks actively throughout a dive. Unknowable, random risks cannot be reduced through advanced planning, and must be dealt with as they occur.

And other risks and risk preferences lurk within your own physiology and psychology. As a diver, you will find yourself in situations where you need to make decisions that will affect your safety. Here are two simple risk preference questions to ponder...

1. It's near the end of a dive in which you had some minor equalizations issues on descent. You felt some pressure in your ears throughout the dive, but not enough to abort the dive. You arrived at your safety stop with less reserve air than planned, and your ears still feel a little plugged. While trying to clear your ears you drop your camera and it sinks to the bottom 5m/15feet below. Your buddy can't or won't go get it and you have one chance to retrieve it or lose it forever. What do you do?

2. You're at the deepest part of the dive with your assigned buddy, maximum planned depth, your tank half full, and it's time to make a 180 degree turn back toward the exit point. After turning, you notice there's current that's strong enough to slow your forward progress. You start to swim harder and your heart rate increases. Your buddy is swimming faster and is pulling ahead of you. You're consuming your air faster than planned. At this rate, your air supply will run out before reaching the exit point. You might have to surface early into a current. You're 2m/6feet above a flat, rocky bottom. What do you do?

There are two kinds of seriously undesirable consequences for you to be aware of and understand: the risk of sudden death and the risk of a serious injury causing long term disability. Consequences can be acute or chronic. Let’s examine some relevant concepts and statistics, then draw some conclusions.

Measuring the risk of dying today

Have you ever heard of a micromort? It’s a unit of measurement, and it measures the risk/probability of your death today as you go about living your life. Everyone alive today is facing a baseline risk of 1 micromort. In simple terms, there’s a one-in-a-million chance that any individual will die today. It’s a very low probability, but it’s not zero. And the risks you take start to increase when you walk through the door to live your life.

Here’s how Wikipedia defines it:

Here's a link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Micromort

The wiki entry is fairly short and the stats are not current, but it contains some fascinating and (in)credible insights, comparing the risk of sudden death that we all face every day when participating in various activities. So let's have some fun with numbers.

Here is a short list of some activities that add 1 micromort to the baseline risk, or approximately doubling the risk of dying today if you decide not to spend it in bed:

walking 27km

riding your bicycle 16km

driving your car 370km

traveling 1600km by jet

going skiing

taking 2 tablets of the drug ecstacy. (that's a wtf statistic!)

Now let's look at some extreme sports :

riding a motorcycle 50km: add 5 micromorts

running a marathon: add 7 micromorts

hang gliding: add 8 micromorts per flight

skydiving: add 8-9 micromorts per jump

And finally (drum roll), if you go on a two-tank dive, add 5-10 micromorts per dive, or 10-20 total micromorts per day, depending on your skill level. Novice divers and inadequately-trained divers are at the high end, facing 20 times the baseline risk of death.

We each have our own unique set of risk preferences. We pick our poisons, so to speak, depending partly on what exhilarates us or taps into our fears. Scuba diving offers plenty of both. So if you want to take up diving, you need to inform yourself and decide in advance on what quality and level of training you will need to keep yourself safe... as well as exhilarated.

How much would you pay to avoid a 1-in-a-million risk of dying today?

Now that we've quantified the relative risk of death by scuba, the question is... How much would you be willing to pay to avoid a 10-in-a-million (10 micromort) chance of death?

The wiki article argues that, generally speaking, when someone makes an initial decision to spend some dollar amount of money on their safety, they are very unlikely to spend significantly more money at a later date to further enhance that level of safety. It’s as if people decide in advance how much risk they’re willing to take, and don’t really budge much from there. People get comfortable with their perception of risk.

The implication for scuba diving is that a typical novice student who enrolls in a cheaply-priced group dive course, offering minimal safety training and skill development, is unlikely to invest later in higher levels of personal training and safety equipment. In other words, if someone is willing to spend a maximum of $500 on an entry-level group diving course, which subjects him or her to a 20 times increase in the baseline risk of death every dive day, then he or she will probably not be willing to spend another $1,000 later for fuller training and safety equipment to cut that risk in half.

This is certainly true in the world of diving. Almost nobody comes back for more training after the Open Water course. And it's not because they don't need any more training. Most divers remain marginally-skilled or choose to drop the sport entirely rather than invest in the additional training that would raise their skills, confidence, safety and quality of experience.

In short, your initial personal and financial investment in diver training is probably all you will ever make. And this initial investment in training will essentially lock you into a lower or higher risk category that you'll not significantly improve on in future years.

Now let’s consider the statistics on dive injuries and fatalities.

Introducing DAN

The authoritative source of data on dive injuries and fatalities in North America is Divers Alert Network, or DAN. https://www.diversalertnetwork.org. Their 2013, 2015, and 2017 reports were the sources for this blog entry.

The data that DAN have collected are not complete. North American (US and Canadian) statistics are fairly extensive and detailed, while foreign and tropical dive incident statistics are more limited. Incidentally, in many parts of the world dive incident reports are deliberately suppressed from public knowledge, for reasons including the protection of local tourist industries. So we don’t often hear about diving accidents, even though they happen every day.

It’s reasonable to assume that the North American dive industry (dive shops, professional instructors/divemasters and tour operators) adhere to higher standards of safety than in many tropical countries, for a variety of reasons including litigation risk and the enforcement of standards by the industry’s leading training organization: PADI. But in 2nd and 3rd world countries, the safety risks that divers are exposed to are likely much higher. There’s no data to support that assertion, but personal experience tells me that this is true.

DAN stresses that their data should not be used to draw specific conclusions and inferences about the risks involved in diving or the frequency of accidents, but rather as a general indication of the types of injuries and fatalities that do get reported.

DAN’s dive injury and fatality statistics

Here are some notable statistics and factoids drawn from various sections of the DAN report.

DAN estimates that there are 3 million divers in the U.S., and that there are about 2 deaths per 100,000 divers per year, with 20 ER admissions per death and many more primary care visits. That's converts to 60 deaths, 600 ER admissions, and thousands of primary care visits every year for those 3 million divers.

In 2013, 68% of all reported dive incidents (fatal and non-fatal) involved a victim with less than 2 years experience from their date of certification.

Over a period of a few years, 12% of reported fatalities were student divers.

64% of all reported deaths were during a pleasure dive, and 8% were during a training dive.

59% of incidents were on the first dive of the day.

When depth of dive was known, 25% of fatalities were in water less than 10m deep and 28% of fatalities were in water 10-18m deep. This means that more than half of fatalities occurred on shallow dives within the limits of a basic Open Water certification.

81% of fatalities involved circumstances that began to go wrong either at the deepest part of the dive (49%), during the ascent phase (9%) or at the surface after the dive (23%). Incidentally, a high percentage of victims found dead on the bottom still had their lead weights in position.

In 2013, 78% of male fatalities and 90% of female fatalities were over the age of 40. (2015- 91% of males and 93% of females were over 40; and 75% of males and 71% of females were over 50). It’s not the wild kids getting themselves killed scuba diving. According to PADI, the average age of novice scuba divers is in the late 30’s.

The medical histories of most victims were not available, but of those that were, 12% had a history of high blood pressure and 5% heart disease.

Body Mass Index (BMI) data were available for about half of all fatalities in 2013. Of these, 47% were overweight (BMI 25-29.9) and 35% were obese (BMI 30-39.9). In 2014, 51% of victims were obese and in 2015, 37% were obese.

Panic, running out of gas to breathe, and rapid ascent were the three most common mechanisms leading to injury and death, each at about 30-31% of the total. I've had personal experience with client panic, out of air situations and barotrauma (ear injuries on descent or ascent). Yes, they're pretty common.

The main causes of death were cardiovascular disease, drowning and arterial gas embolism. Interestingly, decompression sickness (ie. the bends) ranked very low, the 6th most common cause of death. DCS doesn’t often kill, but was involved in 39% of reported non-fatal injuries, the most common of all non-fatal injuries.

Ear injuries were in second place, at 17% of the total reported injuries.

Of all deaths where underwater visibility conditions were reported, 22% were in low viz (<3m) and 48% were in moderate viz (3-15m) environments, or 70% of the total. Unfortunately, this statistic isn’t very useful because the range of moderate viz is too broad. Three meter viz is a very different risk environment compared to 15m viz. In local Howe Sound waters, viz for most of the year is 7m or less. During the summertime the viz is often zero down to the bottom, and dive shops send large groups into this soup every weekend.

Equipment problems were frequently associated with dive incidents, with 25% of all reported incidents happening in conjunction with equipment issues. The most common equipment problems were with regulator free-flow and BCD (buoyancy control device) malfunction. I've experienced both, as well as other equipment malfunctions and failures, such as blown hoses, drysuit floods, hypothermia, dropped fins, lost masks, dropped weight pockets, dead computer and dive light batteries, inaccurate compasses, inaccurate tank pressure gauges and depth gauges, and so on.

The local ocean environment itself presents sudden, unexpected risks. There are no seriously threatening animals in BC waters (except maybe sea lions), but there are stinging lions mane jellyfish, curious biting seals, and defensive ling cod mothers protecting their eggs.

I've done a lot of tropical diving too, where the risks from aggressive or dangerous animals are much higher than in BC. And tourist dive guides don't necessarily explain all the knowable and random risks in their pre-dive briefings. In many countries the diving industry is essentially self-regulated, or faces little to no litigation risk.

All of these problems and dangers require competent risk management strategies and responses for a diver to remain safe.

Analysis and conclusions

It seems clear from the data that individual fitness, dive training and skills, equipment maintenance and prevailing diving conditions can and do explain differences in diving outcomes between safe diving and injury or death.

If you're thinking about taking your first scuba course, the dollar amount of your initial investment in training and equipment will largely determine the amount of risk (in micromorts) that you’ll be taking on as a certified scuba diver for the rest of your diving days. Competent divers face half the risk that a problem will turn into a fatality, compared to weak-skilled divers. When dealing with problems, well-trained divers are much more likely to take appropriate actions. On the other hand, bad decisions often lead to more bad decisions and to dive accidents.

Expressed in hypothetical micromorts, an unskilled novice diver who’s paid a rock bottom $500 price - for a typical large-group Open Water course with minimal training time and minimal direct instructor interaction - is 20 times more likely to die when diving today than if they spent the day in bed. And they’re much more likely to suffer a serious injury that could result in a long term physical impairment.

Would you pay an extra $1,000 for private personal diver training to cut that life-long risk of sudden death or serious injury in half? 99.9% of risk-oblivious novices just say no.

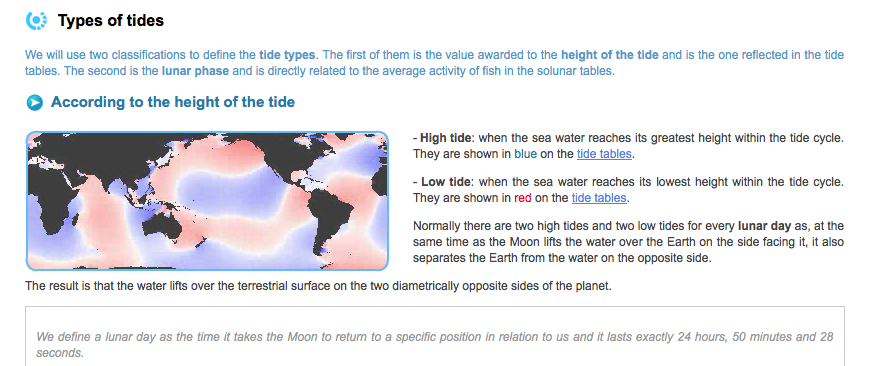

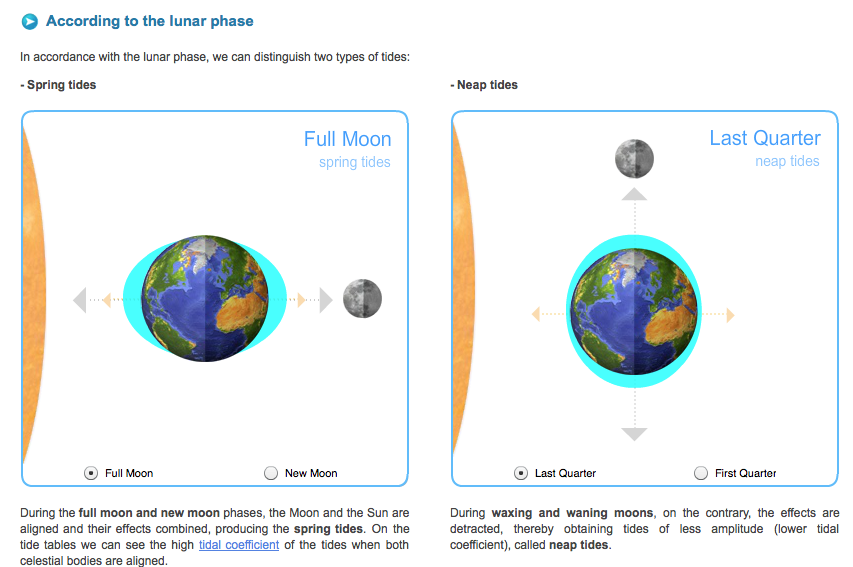

]]>When planning our dives, we always refer to the tide tables to try and estimate when underwater conditions will be at their best. In Howe Sound, the best diving is generally around high tide.

We use a couple of data sources to determine the tides for any particular dive day:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada's website: http://www.waterlevels.gc.ca/eng/find/zone/10

Tides4fishing.com: http://www.tides4fishing.com/ca/british-columbia/vancouver

Here is some basic information about tides: High and low tides, and spring and neap tides

As for currents in Howe Sound, it appears that there is no published source of information. I've been advised by a publisher of nautical maps used by sail boat operators that the basic assumption is for a maximum 1.0 knot current in Howe Sound. I have found in my experience that Howe Sound weather reports, especially wind forecasts, are a useful reference for surface currents and chop.

It's important to note that the area around Porteau Cove and northwards to Squamish is a microclimate, where conditions can be very different from the Southern end of Howe Sound closer to Lions Bay and Whytecliff Park.

]]>

So, for your future reference, you can navigate to the descent point by following a South heading along a line that starts from the "No Camping" sign and passes tangentially by the eastern edge of the island. See the pics below:

Diver entry point into the lake is to the right in this photo.

Arrow marks the diver's float and descent line to the microbialite structures. The float is close to the middle of the lake

Arrow marks the diver's float. It's a southerly heading from this vantage point.

The air temperature was about 37C, people were swimming in 20C surface waters, and bather's were a little amazed to see us put on long underwear, fleecy snowsuits and then climb into drysuits before entering the lake to cool off. But the water temperature at depth was 8C, which is about the same as it is in the ocean around Vancouver in the winter time.

Here's a link to the video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=650bSYfYsNc

]]>

A lack of skill, competence and confidence are cited as main reasons that new divers drop out, which suggests that off-the-shelf group diving courses don't provide enough training. Cheap commodity pricing might draw more people into "checking out" the sport, but it takes proper training and a broader diving education to keep a new diver committed. Commodified training might be turning scuba diving into a bucket list kind of sport, where anyone with $500 to blow can check it out, learn some basics and go on 4 dives, then decide whether to continue with the sport or just drop out of it.

These are my impressions, based on a limited view of the industry. Here's an article taken from Undercurrent, a diver magazine, written by one of the most senior, experienced and well informed people in the diving world.

Incidentally, PADI doesn't discourage or prevent instructors from extending their course offerings to more fully educate and train new divers beyond the bare minimum of an off-the-shelf course. But less than 1% of newcomers are willing to invest in that proper training.

One of the main problems with the diver training industry globally is that there are few barriers to entry, so there are too many dive instructors and dive shops worldwide, competing for market share, mostly on price. This race to the bottom ensures that only the minimum bare- bones training is provided to newcomers, with little or no mentorship.

At Vancouver Scuba diving school, we exist to train and educate divers, not to compete on price for market share and dominance. We've taken the off-the-shelf PADI Open Water Diver course and expanded the training and practice time by 50%. And you'll get this training one-on-one, not in a group of 8 strangers.

Here's a link to Undercurrent.

]]>

]]>As a rule of thumb, you should never consent to buddy with someone that you've never been diving with before.

But don't take my word for it.....here's an article below from Diver Magazine that tells a typical abandonment story.

One of the most frequent causes for buddy separation is the loss of buoyancy control. One diver rises in the water column, out of sight. This happens to me all the time. I watch the student rise out of sight, I wait, hovering in the area where we were separated, and most of the time they regain control and descend back down.

A good rule of thumb is that the diver who loses buoyancy control has the responsibility to regain control and drop back down.

If the diver goes all the way to the surface, then the rule is to stay there and establish positive buoyancy. A responsible buddy will meet you there in a minute or two.

Another common way that divers become separated when swimming side by side is one is swimming faster than the other. The rule there is that the faster swimmer must slow their pace, because the slower swimmer would become overexerted trying to keep up.

A third way that divers get separated is that each is following a different subject of interest rather than a single shared experience. They just swim apart in different directions.

All of these separations can happen on a single dive.

Incidentally, when I was an unskilled novice diver, I was abandoned underwater by my buddies (strangers) in Hanauma Bay, Hawaii, when my low pressure inflator hose started to free flow into my BCD at a depth of 40 feet on the first dive of the day. I didn't know what to do and held onto a coral head until I lost my grip and rocketed to the surface. My buddies just swam away. (These days, I'd disconnect the hose and continue the dive, inflating the BCD orally as needed. And I'd communicate this situation to my buddy). Luckily I didn't end up in the hospital, but I surfaced down-current from the boat and needed to be rescued. Back on the boat, the captain blamed me for leaving my buddies and having to get in the water to rescue me. He said there would be no refund (I hadn't asked for one!), even though the BCD continually reinflated itself to near bursting as it sat on the dive deck. He finally acknowledged the gear malfunction and encouraged me to take another scuba unit and reenter the water alone, because there would be no refund. Despite my lack of skill and experience with diving alone, I put on another BCD, re-entered the water, descended directly into the middle of a large school of small fish... and had my first ever face-to-teeth encounter with a feeding shark. I don't remember my fins touching the the ladder as I breached the surface and launched myself onto the boat deck. The captain looked at me like I was from another planet and insisted that there were no sharks in these waters. At this point he insisted that I was not going back into the water for the second dive and I wasn't getting a refund. When my assigned buddies finally returned to the boat, their excuse for leaving me was that they assumed I wanted to dive alone. This is the reality when diving with strangers at tourist dive sites.

I've witnessed buddy abandonment many, many times as an instructor while teaching group Open Water courses and leading group dives.

I can't tell you how many times I've signalled a diver to ask where their buddy is only to get a shrug of the shoulders in response or a finger pointed toward the surface. But one day, when leading a group of certified divers who were all strangers, on the descent at a site with a steep slope, the response was a finger pointed downwards. I signalled everyone to resurface and emptied my BCD to chase after the missing diver, a middle aged woman who hadn't been diving in a couple of years. I caught up to her at 25m/90 feet as she was tumbling and rolling down the slope. I stopped her tumble and found that the low pressure inflator hose was disconnected so she was unable to power inflate the BCD. (This failure to properly set up the scuba unit ought to have been discovered during the buddy pre-dive safety check). I reconnected the hose and we made our way safely back to the surface. Whew. She was terribly shaken up, but otherwise ok. And I set a policy to always personally double check everyone's gear before every dive.

Novice and inexperienced divers often don't know what to do when a problem suddenly happens, so I emphasize the development of buddy skills in the courses I teach. Very few certified divers have the skills, knowledge and capacity to properly plan a dive or help another diver in trouble. Fewer than 1 diver in 100 is trained in rescue skills. So even if that assigned buddy doesn't abandon you, he or she might not be able to help you. Stick with the professional dive leader/Divemaster until you've evaluated a potential buddy's skills.

Click on images to expand.

]]>

A diver can injure their ears during the initial descent (when pressure changes are greatest), or at any other time during the dive. Effective management of this risk requires that you develop keen ear-monitoring skills (situational awareness) and good technique. And since safety is always the primary objective on every dive, a diver must be prepared to abort a dive if they are unable to equalize fully.

Over the course of my diving life (30+ years) I've experienced and witnessed many ear injuries. A high percentage of these injuries happened during the confined water segment of the Open Water course, in pools where the bottom was less than 5m/15feet deep. It's at this stage that the student is making their first attempts to equalize while possessing no developed buoyancy control skills and very little situational awareness.

It's a painful experience for the unfortunate victim of an ear injury, with outcomes ranging from a mildly annoying weeklong feeling of fullness and dull hearing, through to punctured ear drums, bleeding ears, near drowning, and permanent damage.

PADI Open Water course materials highlight and emphasize the importance of full and proper equalization of your ears on descent and what to do in the event of a reverse block on ascent. At VSds, we think that every novice diver ought to have a full medical and physiological understanding of what's going on in your ears when you go underwater.

The following article is taken from the Divers Alert Network (DAN) website. We urge you to read it closely and practice the various techniques at home. And we urge you to check out DAN. Click on images to expand.

]]>

One way to learn is to break down a complex series of actions into their individual components, then think it through and visualize yourself performing each discrete step. As you practice in your mind, gradually increase your speed until you achieve a fluid motion.

Mask Clearing

There are four discrete steps to take to clear water out of a flooded mask. With practice, these will all flow together.

Look upwards to pool the water at the bottom of the mask.

Press your fingers against the top rim of the mask to hold the seal against your forehead.

Inhale deeply through your regulator.

Exhale with gentle force out your nose...snort!

Repeat as many times as necessary.

To visualize this process, imagine that you're blowing your nose into a kleenex tissue. When you blow your nose, you position your fingers to press against your cheek bones. So when clearing a mask, imagine you're blowing your nose…. but press your fingers against your eyebrows.

What happens when you perform this skill is that when you exhale out your nose, the increased air pressure inside the mask will break the seal against your skin just above your mouth and the air pressure will force the water out the bottom of the mask where the seal has been broken. Too easy!

Mouth breathing

Your nose has only two functions inside a scuba mask: to equalize mask pressure and to blow out any water that has leaked in. Both involve exhalation only. Your nose serves no other purposes, so you need to practice to become a mouth-only breather. Many new divers have some difficulty adapting to this, so I recommend that they practice mouth-breathing at home. Plug or pinch your nose, relax and breathe deeply into your diaphragm. Exhale fully. Wait for the breathing reflex to kick in, then inhale fully once again. Do this exercise for a couple of minutes every day.

Buoyancy Control

Buoyancy control is possibly the most critical dive skill. It's all about developing a situational awareness and skill to control your body position and movement in three-dimensional liquid space, so that you can multitask. You manage your buoyancy using three air vessels, or balloons: The BCD, which contains an air bladder, your drysuit, which is a sealed air vessel, and your lungs (breath control). A 4th component of buoyancy control is effective body positioning and efficient propulsion/finning to keep forces in balance.

Most new divers have some challenges finding and maintaining their balance, achieving neutral buoyancy and staying neutral throughout a dive, especially when trying to hover in place motionless. It’s common for new divers to get caught up and struggle in a zigzag pattern where they can't control their balance, body position, and depth for any length of time. Zigzagging up and down can occur for any of several reasons such as poor situational awareness, slow reaction time, overcompensation for a small change in buoyancy, poor trim and hydrodynamics, inefficient finning and poor breath control.

To understand what is happening to such a diver, visualize a tug of war rope, with forces trying to make you float pulling one way and forces trying to make you sink pulling the other.

Visualize that you’re all geared up and in the water, floating on the surface but not swimming. Forces to make you sink include your body weight plus the weight of the gear you’re wearing. The force trying to make you float is the volume of water that you’re displacing. The more water displaced, the more buoyant you will become. If your BCD is full of air and there is air in your drysuit, you’re displacing the maximum volume of water and will float high on the surface. If you now purge excess air from the drysuit, exhaust air from the BCD and exhale to empty your lungs, you’ll displace much less water, so the weight of your body and equipment will cause you to sink.

For most drysuit divers around Vancouver, it will take 20-25% of their body weight in lead weights in order to sink and be properly weighted.

The BCD contains an air bladder - a big balloon - which is your main tool for establishing and maintaining the balance between the forces to sink and to float. Its’ low-pressure inflator/deflator hose is the equivalent of a car’s steering wheel. You need to be holding onto it at all times (except when checking your gauges) and making lots of small adjustments just like you would driving your car on city streets. As you dive deeper, air in the BCD will be compressed by the increasing pressure, so you need to add air to maintain neutral buoyancy and prevent sinking. Conversely, as you move up from deeper water to shallower water, pressure decreases so the air in your BCD will expand. You will need to exhaust air from the BCD to maintain neutral buoyancy and prevent an out-of-control ascent.

Your drysuit is connected to the tank by a low-pressure hose on the regulator. You control the volume of air inside the drysuit with an inflator button and an exhaust valve, like with the BCD. To maintain neutral buoyancy, add air when you're descending and exhaust air when ascending. Use your right hand to deploy both the inflator and deflator buttons.

If you're wearing a drysuit and you let your arms go weak/limp and fill up with air, you'll create bulging balloons of air at your shoulders, with little air around your lower body. This will throw you off-balance, and will often cause you to become positively buoyant. And it can cause the air bubble to escape through your neck or wrist seals, which will let water in to the drysuit. Keep your arms tucked in close to your body!

Drysuit divers will set the drysuit exhaust valve to the closed position during the descent, then open up the valve when they get into a horizontal position at depth. Once the exhaust valve is opened, the drysuit will automatically exhaust excess air. This means that anytime the diver feels positively buoyant, all they have to do is rotate/roll their left shoulder upward for a couple of seconds to let the excess air exhaust itself, then rotate back to down to level their shoulders.

Propulsion techniques

All your underwater propulsion comes from the action of finning. It's a waste of energy and tank air to use your arms for propulsion. And multitasking is impossible if you're doing the breaststroke underwater. Proper, effective and efficient finning techniques take time and practice to develop. At first, you’ll need to consciously think about and manage your finning technique. After a while, it’ll become second nature. The two main techniques are the flutter kick and the frog kick, which are used primarily for straight-ahead forward propulsion. But there are other, more advanced finning and maneuvering skills that you should be aware of too.

Please read this Wikipedia entry, then continue below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finning_techniques

Position for flutter kick:

Position for frog kick:

To maximize your propulsion potential, you need align your body hydrodynamically to minimize water resistance. This means that your body should have a 0-30 degree upward angle from a level horizontal position, with your shoulders higher than your knees, so that you can look forward without craning your neck. Keep your back moderately stiff/arched. Knees are half bent, so your feet and fins are higher than your knees. Don’t let your feet drag you down into a steep angle…that’s bad hydrodynamically and will force you to swim harder alongside your more-hydrodynamic dive buddy. See the picture below where the diver’s feet are dragging and shoulders are elevated so that there’s a big bubble of air…

When using the flutter kick, keep your knees flexible, and ankles loose on the linear plane, but stiff laterally. This is because if weak ankles allow the fin to wobble or cut diagonally though the water, you’re in effect kicking with a fin that’s no wider than your foot. Propulsion is best when you follow through and not cut the fin-kick cycle short. Glide between fin kicks, until your forward movement loses momentum. Kick and glide, kick and glide. This will keep your heart rate down and improve your air consumption.

For slower swimming speeds, for example when you’re scoping out a small area, thrust comes mainly from your calf muscles, or below your knees, because you don’t need the full energy that comes from your hips and thighs. The thrust power comes from the action of straightening your leg…the downward thrust. While one leg is thrusting downward, the other leg is bending upward. Alternatively, use the frog kick.

When ascending vertically straight up, like at the end of a dive, keep your legs straight but loose, your toes pointed downward and your ankles loose linearly but stiff laterally, thrusting from the hips.

Many new divers become fatigued by water resistance against their fins as they swim around. To avoid thigh muscle burn, many novices take a shortcut and swim like they’re riding a bicycle or climbing a ladder, as discussed in the wiki. Of course they need to kick at twice the speed to make any forward progress, so this finning technique is very inefficient.

Most 40 minute dives cover a distance of 500m or less. Some of this bottom time will be spent hovering in one spot, some time swimming slowly and some time swimming faster between points of interest. Different finning techniques can be used for each situation.

It’s a waste of energy to use your arms for propulsion, so the proper swimming position is with both arms folded across your torso to minimize drag and support your balance. Arm movements are really only useful for close-in maneuvers and sharp turns.

Situational awareness when inflating or deflating the BCD or drysuit: estimating volume changes by proxy (sound)

It's not possible to estimate the physical volume of air that's being pumped into or exhausted from the BCD or drysuit at any given moment during a dive. You keep track of this net volume by proxy: by estimating the number of seconds that you've pressed the inflator button or exhaust button. The only way to do this is by listening to the hissing sound that's made by the inflator valve, and the bubbling sound made when air is exhausted.

It’s important to add or exhaust air in small increments, to avoid overcompensating and flinging yourself in the opposite direction. The proper way to hold the BCD inflator hose is in a pistol grip, with fingers and thumb positioned to press the inflator and exhaust buttons as needed. With this kind of grip, you will be able to make quick adjustments and even be in position to inflate your BCD orally if necessary.

If you're adding air to the BCD to offset negative buoyancy, do it in one-second increments and listen to the hissing sound to estimate this duration. Use your inner voice to count "one thousand and one". Wait a few seconds to determine how much this additional air has changed your buoyancy. If you're still negative, press the inflator and count "one thousand and two".

If you need to exhaust air, lift your left arm as high as it will go as you press the exhaust button, to make sure that air is efficiently exhausted from the BCD. Watch the bubbles as you exhaust the air, to see how much you have dumped. And listen to the bubbling sound this air makes as it exits the BCD, to estimate the number of seconds of air that you've exhausted.

While some new divers tend to positive buoyancy, others tend to keep sinking. Resist the temptation to swish your arms when you’re sinking. It’s too little compensation and a waste of energy. Instead, squeeze the inflator button for one second, wait a moment to see if you've added enough air, and if you need to add more then add air in one-second bursts.

don’t swish, use the inflator

Body positioning, centre of gravity, and centre of buoyancy

Most body weight and lead weight are located around a diver's mid-section, with lead weights positioned close to the belly. This is the diver's centre of gravity (your core), and it acts like a boat's keel. The diver's centre of buoyancy is located above the centre of gravity, around the lungs and the BCD's air bladder. In general, the greater the vertical distance between your centre of gravity and your centre of buoyancy, the more stable you will be and the easier it will be to stay balanced. This is one of the reasons why wing-style BCD’s are generally preferred over jacket style BCD’s by serious divers. In a wing style, the air bladder is totally behind you, while in a jacket style, the air is distributed mostly around your sides, closer to the centre of gravity.

When a diver is swimming along, it's helpful to use a visual "spotting" technique to support proper body positioning and to provide a visual destination to swim towards. This involves looking ahead in your direction of travel, seeking to visually spot and fix something in the distance that you can swim towards. This technique helps to maintain situational awareness of your depth, speed of travel, visibility conditions, etc.

Breath Control

Breath control is a critical dive skill that can only be mastered over time. While the course manual suggests that you should breathe normally underwater, it’s a different kind of normal than the way we breathe on the surface. The skill involves consciously managing your respiration to oxygenate your body efficiently, and effectively .

The basic breathing pattern while swimming along involves saturating your lungs effectively with oxygen, so you should :

Inhale slowly and deeply for 3 to 4 seconds, fill your lungs

Hold the air in your lungs a for couple of seconds, to maximize oxygen absorption

Exhale slowly and fully for 3 to 4 seconds, empty your lungs

Wait for the breathing reflex to kick in…

The breathing reflex is controlled unconsciously by the body’s need to keep the partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in arterial blood at a constant level. Your body will tell you when it’s time to inhale. Don’t over-breathe, it’s inefficient management of your air supply.

The basic breathing pattern can be interrupted at any time when necessary to perform maneuvers.

Overexertion will overwhelm a diver’s ability to maintain the basic breathing pattern. This can give a diver the feeling that they’re not getting enough air from the regulator…oxygen starvation. If this happens, then the diver must slow down, or stop and rest to get the heart rate and breathing back under control.

Incidentally, good breath control skills will enable you to fine tune your vertical position in the water column without adjusting the volume of air in your BCD or drysuit. This is an especially important skill for photographers when hovering around a subject.

]]>

Whether you are gearing up for diving in BC or in tropical warm water, there are four categories of gear that you will be needing and using:

- Personal gear - mask, snorkel, fins.

- Scuba unit - regulator, BCD, lead weights, air cylinders.

- Exposure protection - wetsuit, drysuit, undergarments, hood, gloves, booties.

- Accessories - tools, safety equipment, communication aids, hobbies and spare parts including: computer, compass, dive light, knife, slate, signalling sausage, marine radio/GPS locator, gear bags, tool box, etc.

The cost of fully equipping yourself for diving in BC can easily reach $5,000 for middle-of-the-road quality, so you will likely prefer to budget and accumulate your gear incrementally. What factors should you consider and what should your priorities be?

- Firstly, you must understand that whether you own or rent the gear you carry into the ocean there will always be some risk of equipment malfunction. Dive shop rental gear is by definition used gear, much of which needs regular maintenance and repair. Some rental gear is very old and all of it gets mistreated. We strongly urge you to fully inspect and test all rental gear before you take it into the ocean. Don't trust blindly. If you don't like some piece of equipment you've been given, ask for a different one. And if you decide to buy some gear, recognize that you are taking on the responsibility to service and maintain it to manufacturer standards.

- Secondly, whether you own or rent your gear, dive gear can and does break down, and it does malfunction. Busy dive shops all over the world often fail to notice or consciously ignore deteriorating or malfunctioning equipment. Scary but true. Often, no repairs or maintenance are performed before the equipment experiences a failure. Believe me.....I have many stories about rental gear failures from my own experiences as an instructor and international traveller, including gear failures underwater. But you can mitigate a lot of risk and disappointment by using your own gear and servicing it regularly.

- Pricing is important, but buying from the internet costs you more over the full lifecycle of the equipment. It's smart to establish an ongoing relationship with a dive shop operator. Buy your gear and get it serviced at the same place. You will not only be better informed, you will get better, faster service and pay lower gear maintenance costs than if you buy your gear from the internet and then try to find someone qualified and licensed to service it.

Equipment Priorities

1 Buy a premium, well-fitting mask and spare mask strap. $100-150. It will last you 10 years or more. It fits easily into luggage. You can also use it for snorkelling. Nothing sucks the fun out of diving more than an ill-fitting leaky mask. Every diver has a unique facial profile, nose shape and size and visual acuity. It's imperative that you wear a mask that fits, feels comfortable and allows you to see everything that you need and want to see. Some models will accept prescription lenses, which usually cost an extra $200.

Snorkels cost $30 to $80.Unless you plan to do a lot of snorkelling, buy the cheapest snorkel you can find and a spare snorkel holder made of soft rubber/silicone, not hard plastic. Plastic snorkel holders break. The retail markup on snorkels is crazy, and for most divers it's not worth the expense to buy a premium dry snorkel. You can buy a snorkel directly from Chinese manufacturers, on Ebay, for $15 or less, delivered.

2 Buy premium fins, preferably split fins, and a spare fin strap. $200+. Bungie straps and spring straps are worth the extra expense. Diving with split fins will give you a consistent, predictable, soft ride, will minimize overexertion and thigh burn and will therefore maximize your swimming comfort and bottom times. Some fins come with a lifetime replacement warranty on both the fins and the fin straps. You'll never have to buy another pair or pay for maintenance. And you can avoid the spare straps if you get fins with spring or bungie straps.

3 If you decide to take the plunge and invest, buy the gear that you need to be 100% confident in its functionality and reliability, and can take travelling with you anywhere: a regulator with depth and pressure gauges, a compass and a computer. Total $1500-$2000. You'll also need some spare parts and tools for minor maintenance jobs, spare mouthpiece, low pressure hoses and computer battery.

The annual maintenance cost for a regulator is about $100. The regulator delivers air from the cylinder to your lungs for breathing, to your BCD and dry suit for buoyancy control and to your gauge console for monitoring tank pressure. It is imperative that this critical piece of equipment be in tip-top working condition at all times, so if you buy one, be sure to get it serviced annually, whether you're diving actively or only occasionally. If you haven't been diving in 6 months or more, get the regulator inspected before using it.

Most gauge consoles come equipped with an air pressure gauge and a depth gauge. These two gauges can lose their accuracy over time and might eventually need to be replaced. Air pressure gauges can be inaccurate by up to 10% and I know a diver who inadvertently descended to 180 feet although his (rented) depth gauge indicated that he was at 130 feet. The gauge console might or might not contain an integrated compass. If it doesn't, then buy a large, wrist-mounted or retractor-mounted compass. It's standard equipment for anyone who takes the Advanced Open Water course, but everyone ought to develop superior navigation skills right from the start. Recently, I was taking a client on a navigation dive. Their rented gauge console held a compass that was 180 degrees out of whack. So I repeat: if you are renting gear, test all of it before taking it into the ocean.

The highest priority accessory is a dive computer, which gives you real-time data on your depth, bottom time, remaining no-decompression time, surface interval nitrogen desaturation, and much more. Good computers can be purchased for under $400. Before you buy a computer, be sure to learn the details about it's dive table algorithm. Some computers have extremely conservative dive tables that might unnecessarily restrict your bottom times and safe ascent rates. Your dive computer will become your primary depth gauge, with the console's depth gauge becoming your backup in the event of a computer failure.

4 Buy a main dive light, a small backup light, a knife tool and a writing slate next, to see true colours, keep track of dive plan details, carry a useful tool underwater and support better buddy communication. $500-$700 total.

5 It's not critical to have your own BCD, but rentals should be thoroughly inspected and tested before use. Most dive shops offer regulator/BCD package deals that offer some savings over buying them separately, but if your budget forces you to choose between a BCD and a computer, buy the computer first. BCD's cost $500-700, with annual maintenance cost of $100. The two main styles of BCD are the jacket and the harness/wing styles. Jackets will have the air bladder positioned mostly around your torso area, whereas harness styles have the bladder in the back, behind you. Harness styles are less constricting on your chest, whereas fully-inflated jackets can feel tight and constrict your breathing. The two styles can have different characteristics in the water. Harnesses might tend to make you face-plant on the surface while keeping you more horizontal when underwater. There are advantages and disadvantages to each style, but serious divers tend to prefer the harness.

6 Lastly, exposure protection can be rented in BC waters until you commit to being an active diver. For tropical diving, I recommend that you buy your own wetsuit, to ensure proper fit and function as well as for hygienic reasons. Most dive shops never sterilize or disinfect their rental wetsuits between uses, which I find gross because of the dead skin and urine. But, hey, that's my hangup.

Ocean temperatures can vary from around 30C near the equator to 6C at depth in BC during the Winter season. As an international diver, I have two drysuits and two wetsuits in my gear chest, along with several pairs of booties, hoods and an entire bag devoted exclusively to gloves. It can sometimes be difficult to find a rental exposure suit that fits you properly unless you are very close to a standard size. Improperly-fitting exposure protection won't keep you warm, and loose dry suit seals will result in leaks and flooding.

Dry suits require regular maintenance and repairs. Neck and wrist seals wear out and fail in about 100 dives. Inflator and deflator valves eventually start to leak. Zippers wear out and break. If you buy a dry suit, expect to spend $1500-3000 for suit, booties, hood and neoprene gloves, and an average of $200 per year on maintenance. I recommend dry glove systems, especially in the Winter.

If you buy a shell style suit, you will need to wear base layers and heavy undergarments. Most people will already own some of these items, but it's definitely worth spending $500 on a good quality undergarment.

Very few active divers wear a wetsuit in BC, but the best time of year to wear one is in the Summer. A heavy integrated wetsuit (suit + hood), or semi-dry suit, booties and neoprene gloves will be about $1000. The problem with wearing a wetsuit in BC is that for most of the year it's difficult to warm up between dives. So a diver gets cold much faster on the second dive.

7 Cylinders and weights are virtually identical everywhere and there is no need to own them before becoming a serious and independent diver. Cylinders cost about $250 to buy and $10 per fill. They require an annual inspection as well as hydrostatic testing every 5 years. Most shops will rent full cylinders for about $20 each.

Lead is basically sold by weight, at about 3-5 times the price of the metal. Beware of huge retail markups.

8 Dive shops will typically offer full gear rental for about $100-120 per day. So do your math and weigh all the various factors including your risk tolerance and the number of days per year that you hope to dive.

]]>

I quit that course when I was required to flood and clear my mask for the first time. Kneeling in shallow water in the pool, I pulled the mask from my face, snorted water up my nose, coughed out the regulator, swallowed more water, stood up, coughed my guts out, wiped the snot from my face and left the pool without looking back. The instructor never stood up to see how I was doing. I told the front desk on the way out that this sport just wasn't for me. I can't do this.

Gary harassed and shamed me until I eventually went back and learned enough skill to pass the course. I never completed the swim test.

I only ever went diving with Gary twice. On my first dive as a certified Open Water diver, he took me into a 5 knot current at Active Pass and planned a 30m/100 foot free descent without dive lights from a live 16 foot aluminum boat, seeking to land on a seamount and gather scallops for dinner. Yikes! Woohoo! We missed the first time, dropping to 35m/120 feet and drifting for a few minutes into the Georgia Strait before he finally decided that we'd been carried past the seamount and gave me the ascent signal. The boat picked us up a mile from the point of entry. We swapped tanks and Gary nailed it the second time. There were thousands of scallops resting on the dimly lit seamount and as we landed they started to swim off like a vast flock of video Pac-Men. This was the moment that I learned how to laugh into a regulator. Swimming and crawling along into the still-strong current, my ill-fitting mask half flooded, we filled our goodie bags and I had my first close encounter with a huge Giant Pacific Octopus swimming in open water. A totally awesome, terrifying and overwhelming first two dives! And a great feast with stories to still tell 30 years later.

I know now that I never should have agreed to do that dive and that Gary was irresponsible for taking me there. It was way off-the-charts beyond my skill level. But I'm very glad to have done it. I eventually lost touch with Gary and have never been able to thank him. 30 years later, scuba diving is very much a core pursuit and value in my life.

]]>